Logical Split Disk — Technical Overview & Demo

This article unpacks the implementation details of Project 1’s core technology—Logical Split Disk (LSDisk)—showing how low-level sector remapping achieves true isolation and multi-disk virtualization on a single physical device, and demonstrating native cross-OS compatibility and real-world value. I built a USB controller that reclaims control of the storage device and turns one flash drive into four.

A. Introduction

Today, I want to share the result of a long-standing obsession: a USB controller I built by hand. It does one thing, but that one thing matters—it gracefully takes back control of a storage device (its identity, every sector’s read/write permissions, and the data itself) from the host and returns it to the device’s owner. The most tangible outcome is that an ordinary USB flash drive or SD card can be sliced into multiple disks that appear completely separate to the host. On my prototype, I implemented four independent disks.

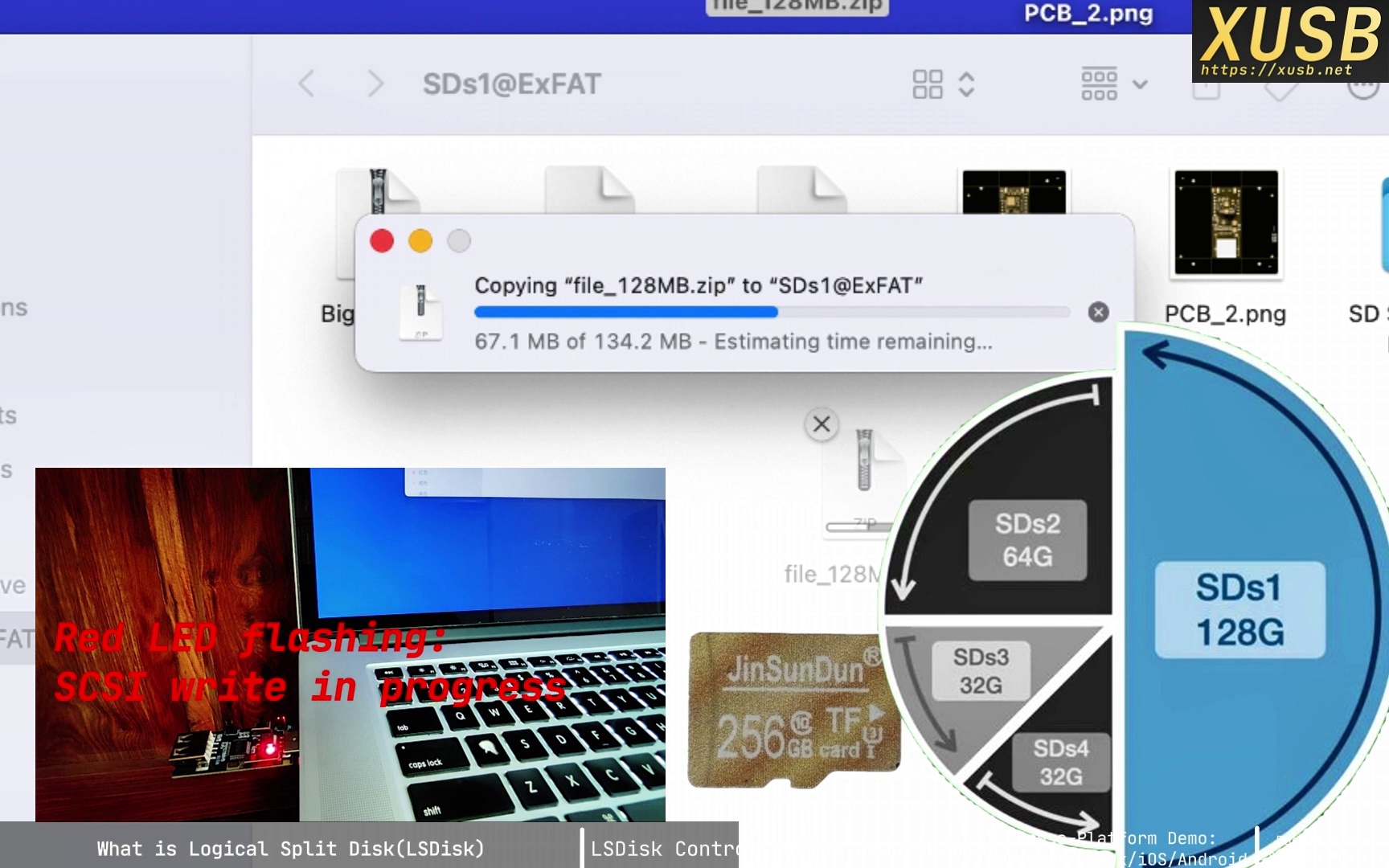

(Logical Split Disk (LSDisk) - Mini Demo overview and driver-free compatibility tests on Windows, macOS, Linux, iOS/iPadOS, and Android. Full demo video at the end of the article.)

B. It all began with one question: we should have full control over storage devices

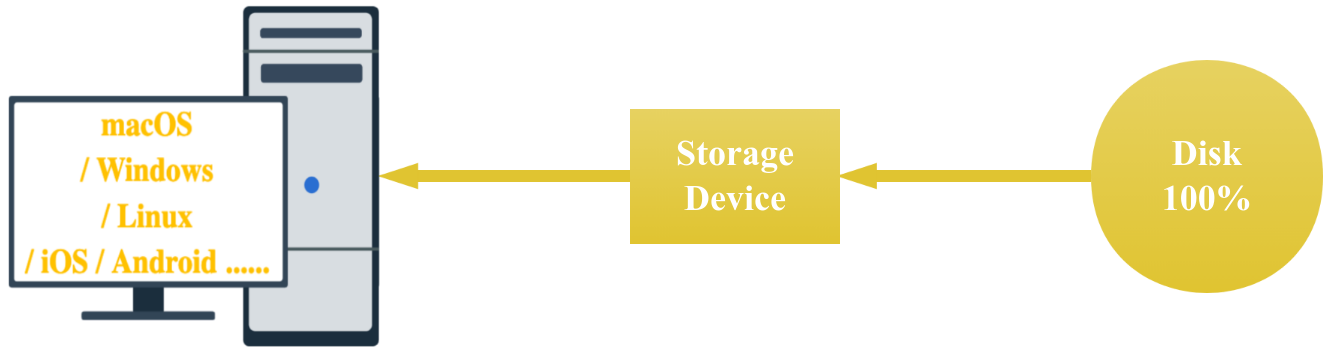

We’re used to this flow: plug a USB drive or SD card into a computer and let the operating system take over. We become “third parties.” If we want to manage the device, we can only ask the OS for partitioning or install security software. That model surrenders low-level hardware control and forces increasingly complex host-side software to do work the hardware should do—data isolation, multi-boot, and protection. These software solutions don’t offer real control, are hardly elegant, and can be impractical (e.g., you can’t install security software on someone else’s computer). So I set out to reclaim true control by designing a “hardware proxy”—a USB controller that governs the commands a host sends to the storage device.

(One loss-of-control scenario: the host accesses the entire space; the device owner cannot decide what portion connects to the computer.)

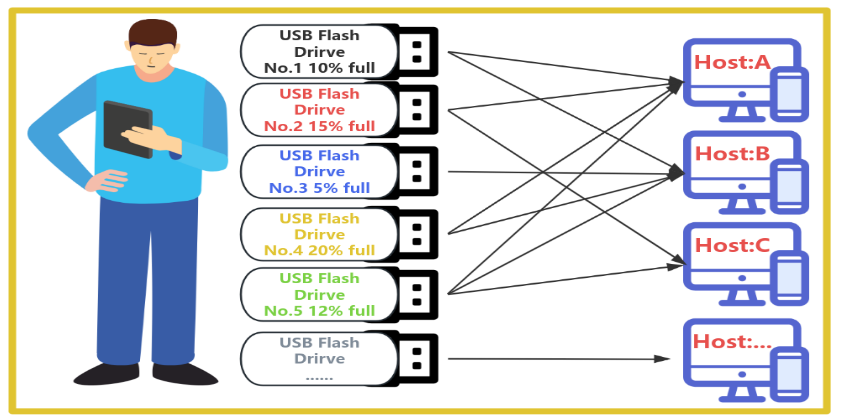

(Even with plenty of free space, you end up carrying multiple drives to match different use cases.)

C. Core idea: control every sector and assert hardware sovereignty

While studying how to govern host commands to storage, I found several interesting use cases. One I call Logical Split Disk (LSDisk). It’s fundamentally different from traditional partitioning because it works at a lower layer. The medium can be cut into N independent devices; each logical disk is a fully separate device with its own LBA 0 (Master Boot Record, or a protective MBR under GPT—GUID Partition Table) and can be selectively attached to the host (the computer). Its mechanism can be summarized as two key low-level actions during USB device enumeration:

1. Define boundaries

When the host asks “Who are you? How big are you?” (e.g., SCSI—Small Computer System Interface—READ CAPACITY (10)), the controller intercepts the request. Instead of passing through the flash’s true physical capacity, it returns a custom size according to logical boundaries preset via DIP switches. To the host, anything beyond that boundary simply doesn’t exist.

2. Sector control

For any read/write I/O (e.g., SCSI READ (10)/WRITE (10)), the controller again intercepts and validates the Logical Block Address (LBA) before mapping it within the active logical disk’s physical sector range. To the host, each logical disk looks like a discrete hardware device with crisp boundaries. Unselected sectors are never visible to the host—at any time.

D. Visualizing the details

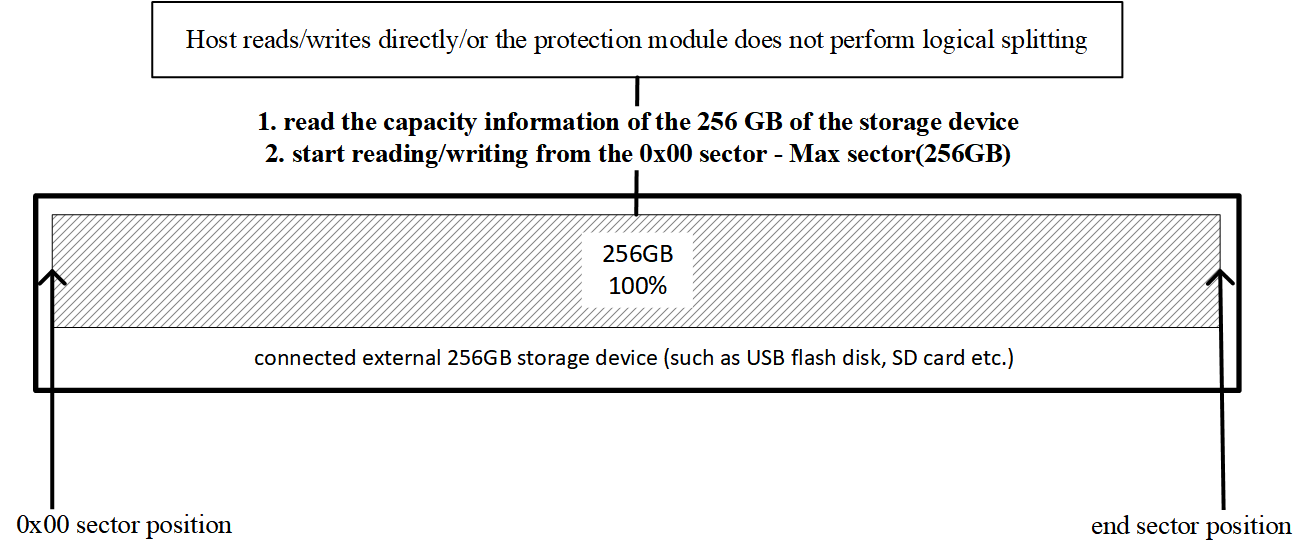

1. The typical case

Take a 256 GB SD card. When the host connects, it first queries capacity and hears “256 GB.” From that point on, the host considers itself free to read/write any sector from address 0 to the end—no constraints.

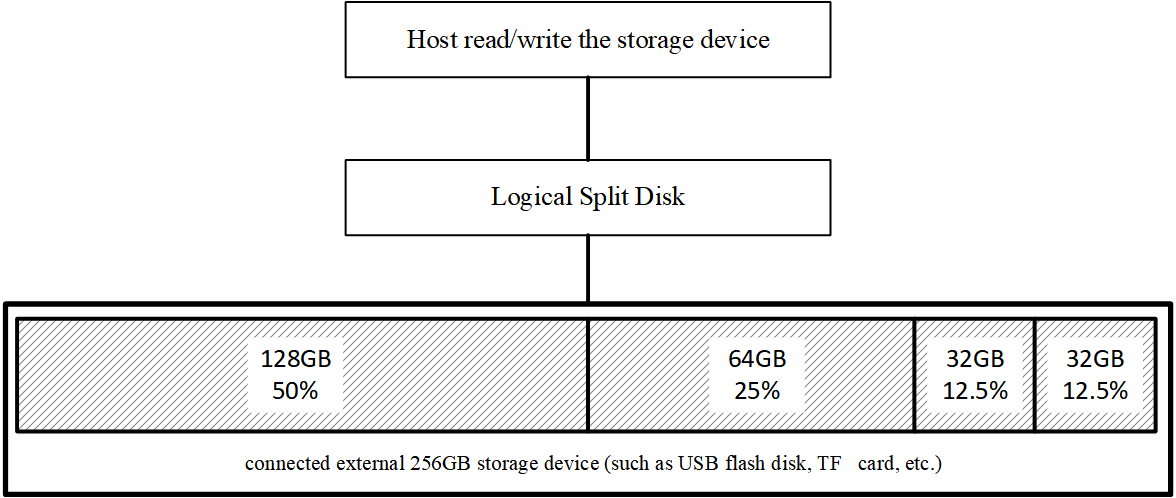

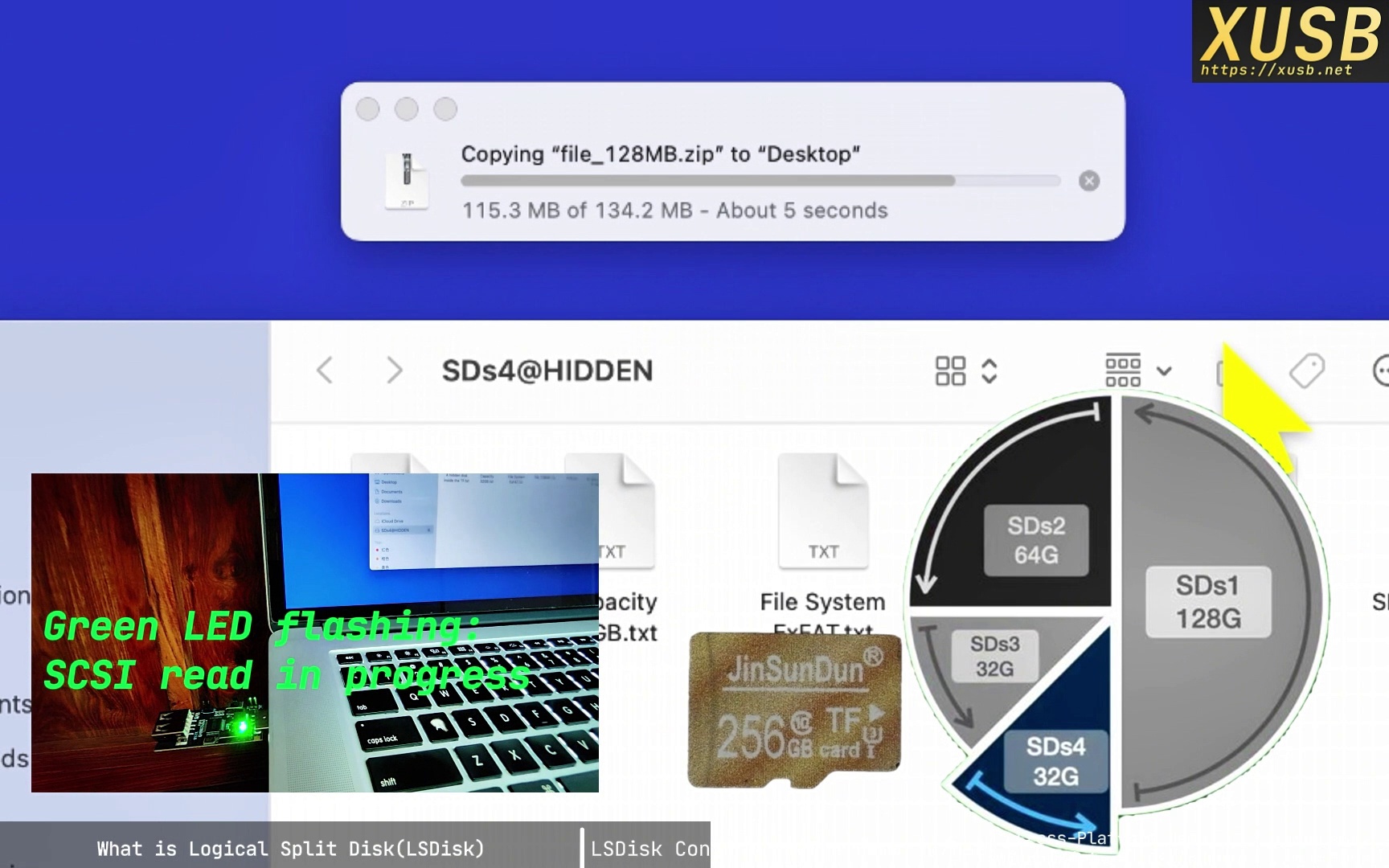

2. With Logical Split Disk

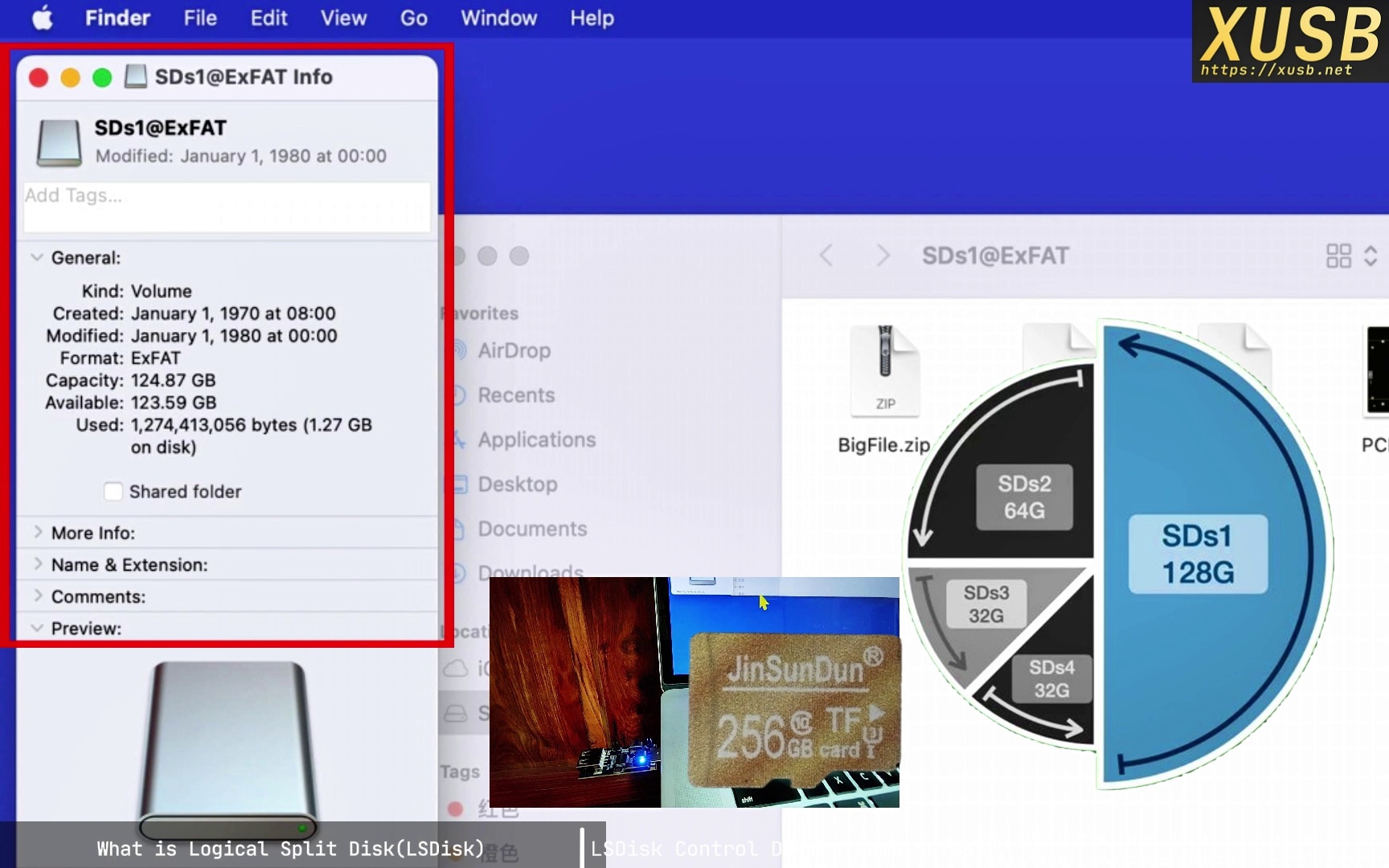

LSDisk changes the interaction. By inserting a control layer (the hardware proxy) between host and medium, the same 256 GB device is presented as four independent disks—say 128 GB, 64 GB, and two 32 GB drives. The host is now talking to a virtualized hardware layer, not the raw medium.

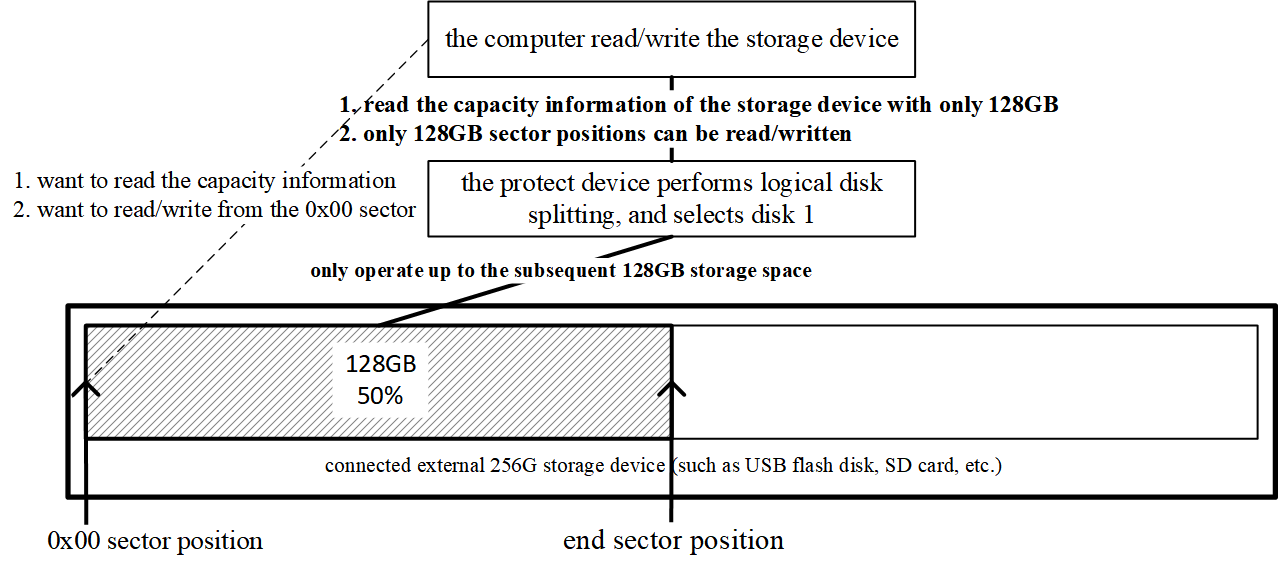

3. Selecting logical disk 1

If the user selects disk 1, the controller answers capacity queries with “128 GB,” not the full 256 GB. The host believes only 128 GB exists and strictly confines all I/O to that boundary; the rest remains unknown.

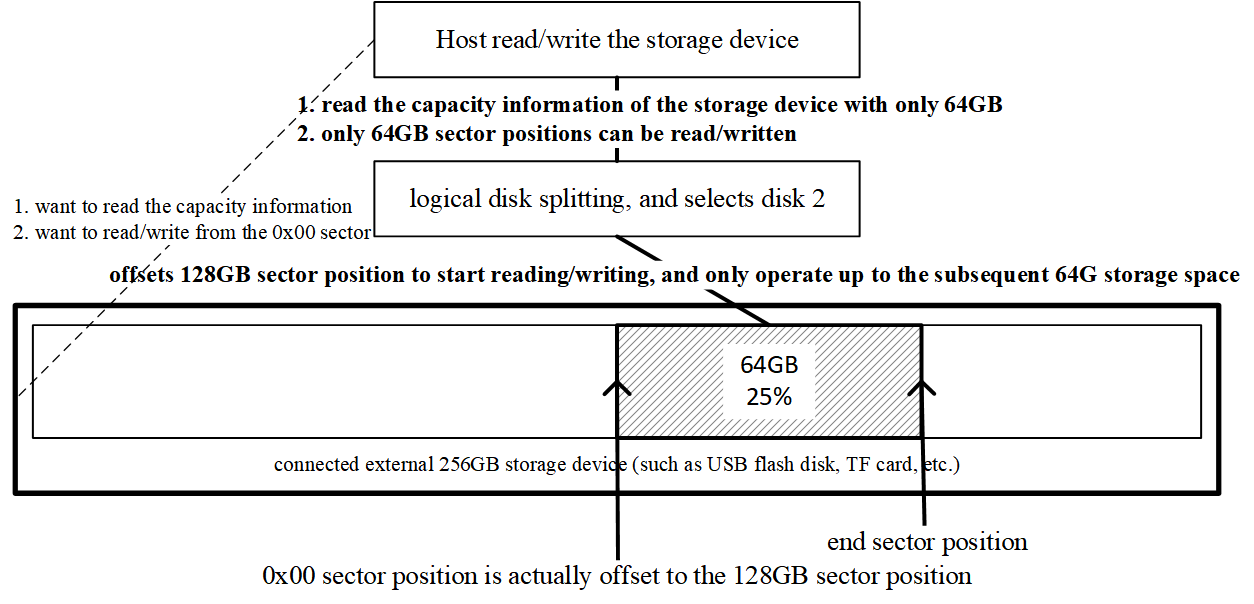

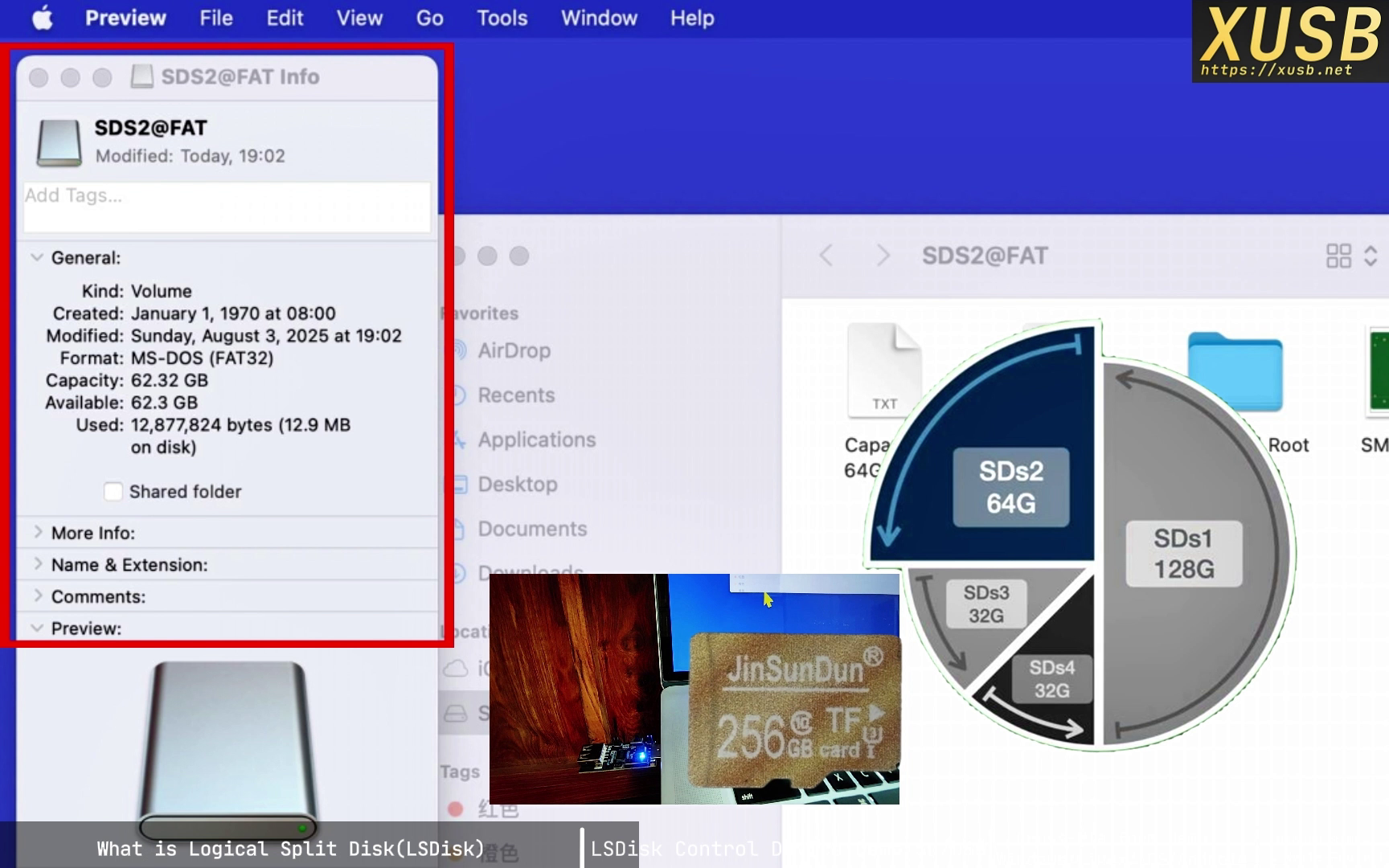

4. Selecting logical disk 2

When disk 2 is selected, the controller reports “64 GB.” If the host writes to logical sector 0, the controller transparently adds an offset so the write lands at the actual physical start of the 64 GB region (immediately after the 128 GB region). The host stays in its logical worldview, unaware of the remapped addresses.

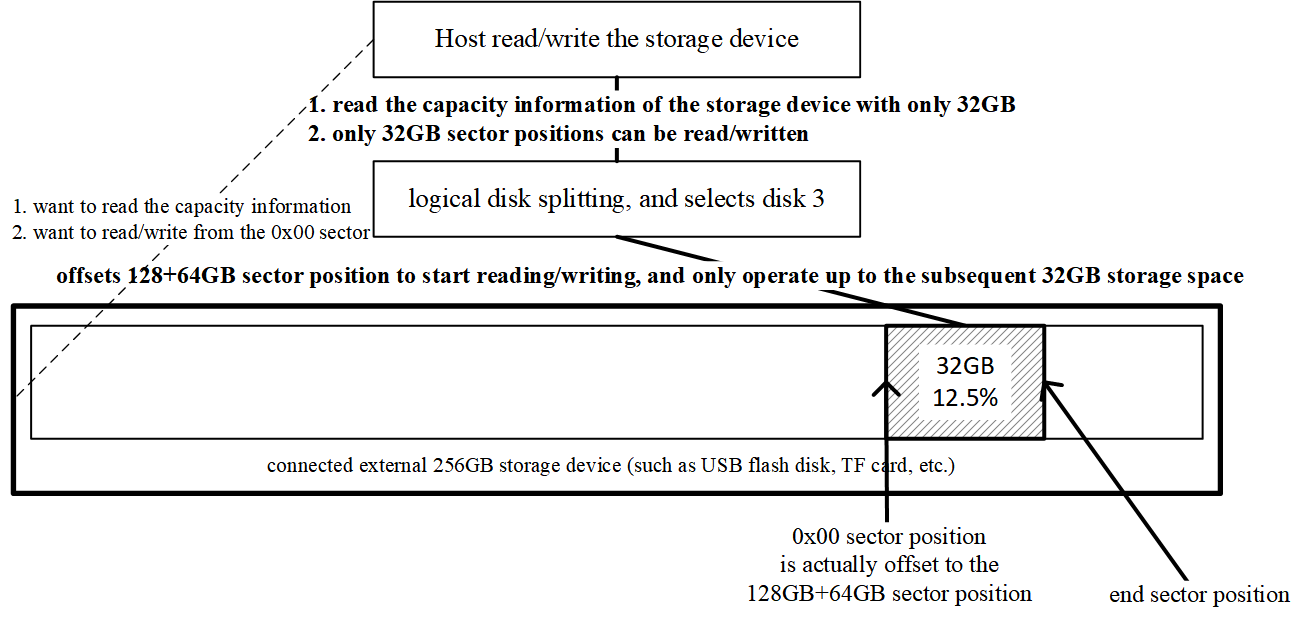

5. Selecting logical disk 3

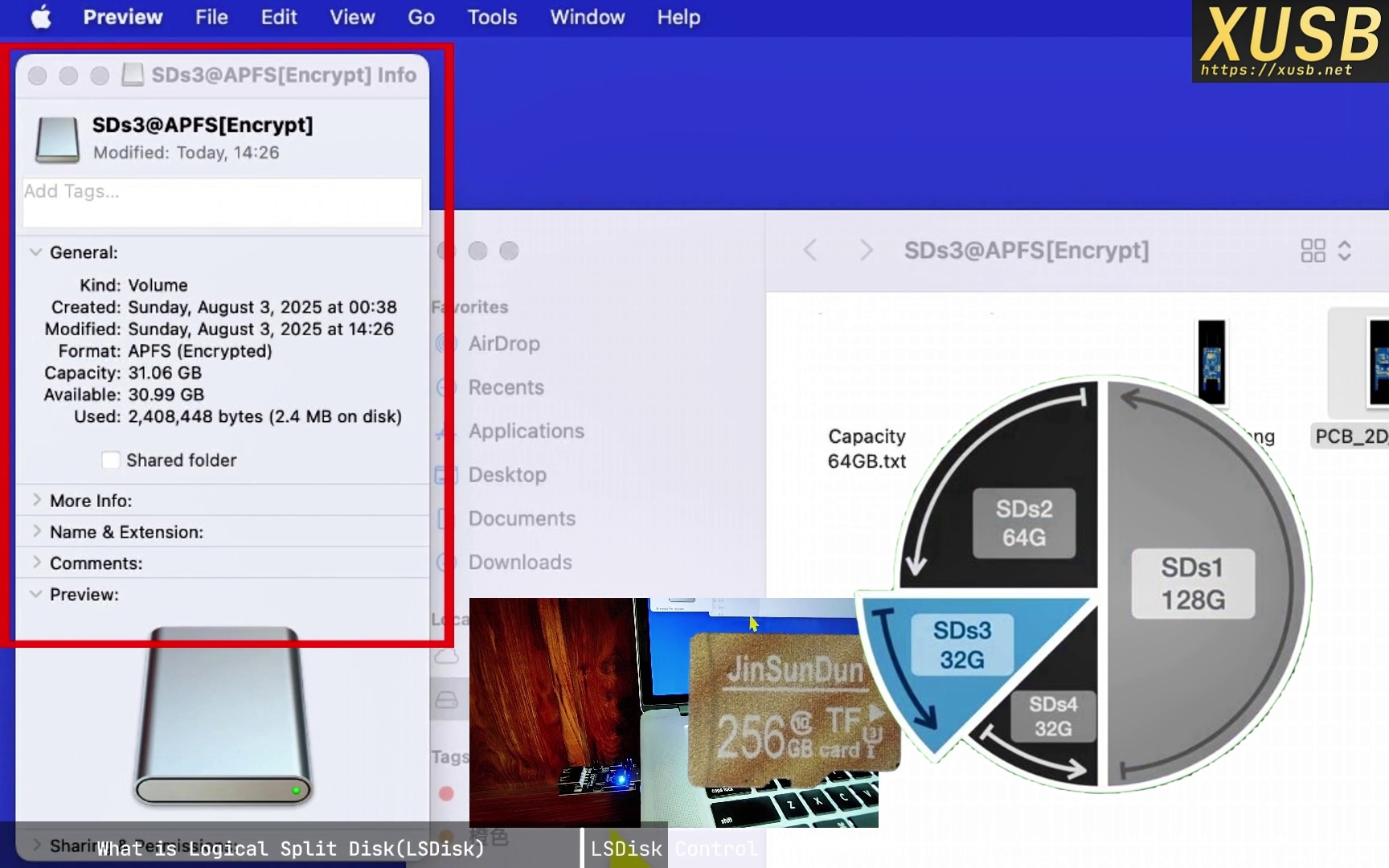

The same logic applies. Selecting disk 3 yields a 32 GB capacity. When the host writes to its logical sector 0, the controller applies the combined offset—128 GB + 64 GB—so data lands in the correct physical location. To the host, it’s just a standard 32 GB drive.

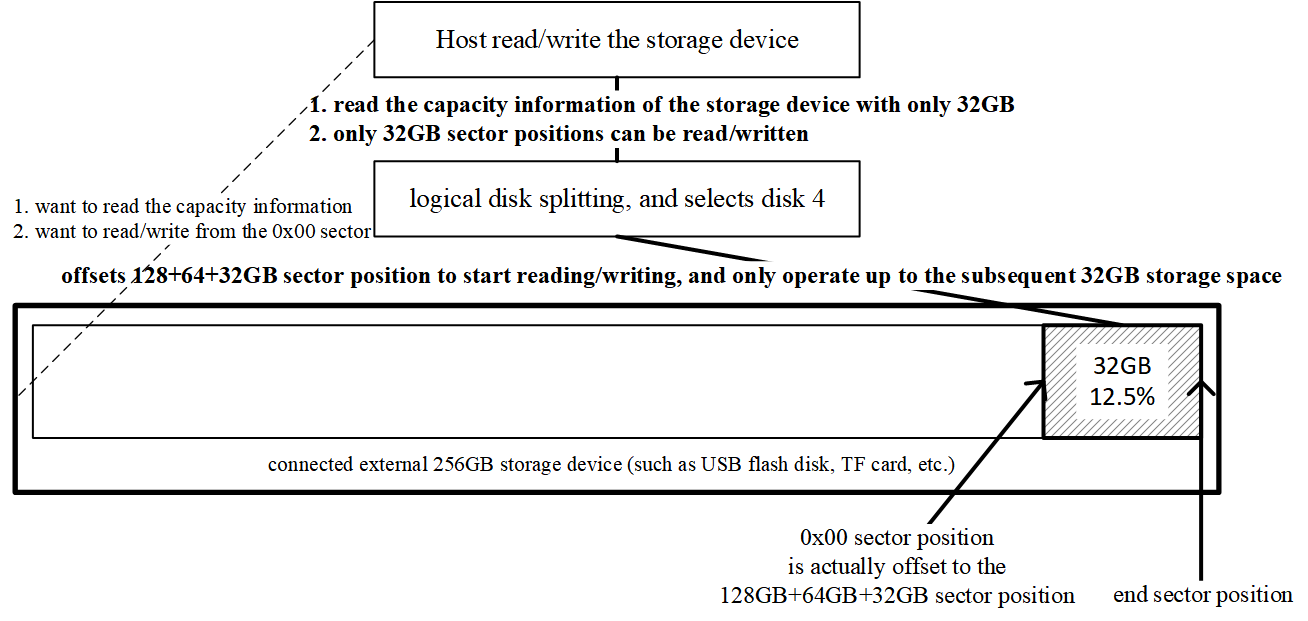

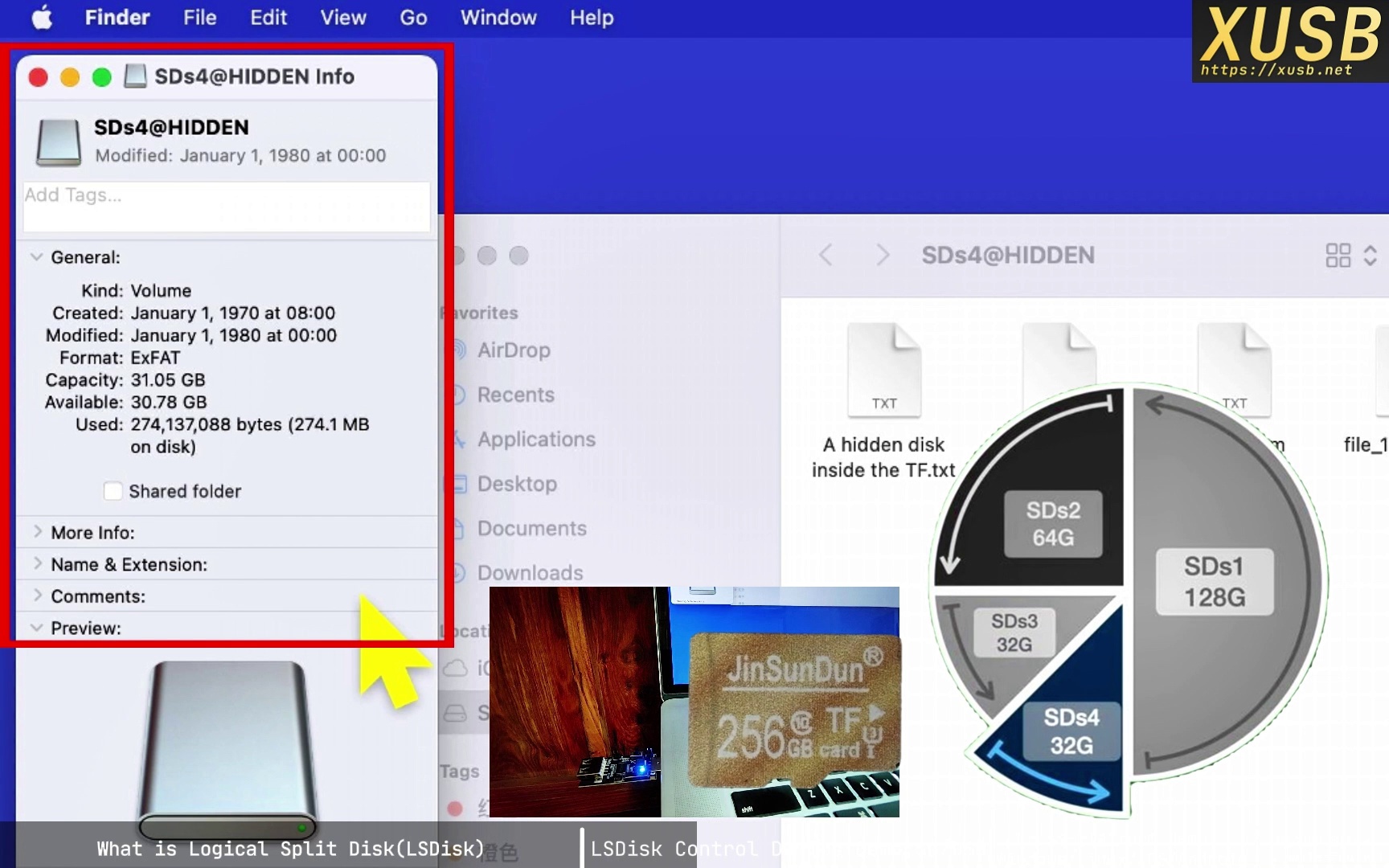

6. Selecting logical disk 4

Likewise for disk 4: the controller presents a 32 GB drive and redirects all I/O to the last region. With elegant SCSI-command interception and redirection, one physical device can appear as multiple, fully isolated hardware drives.

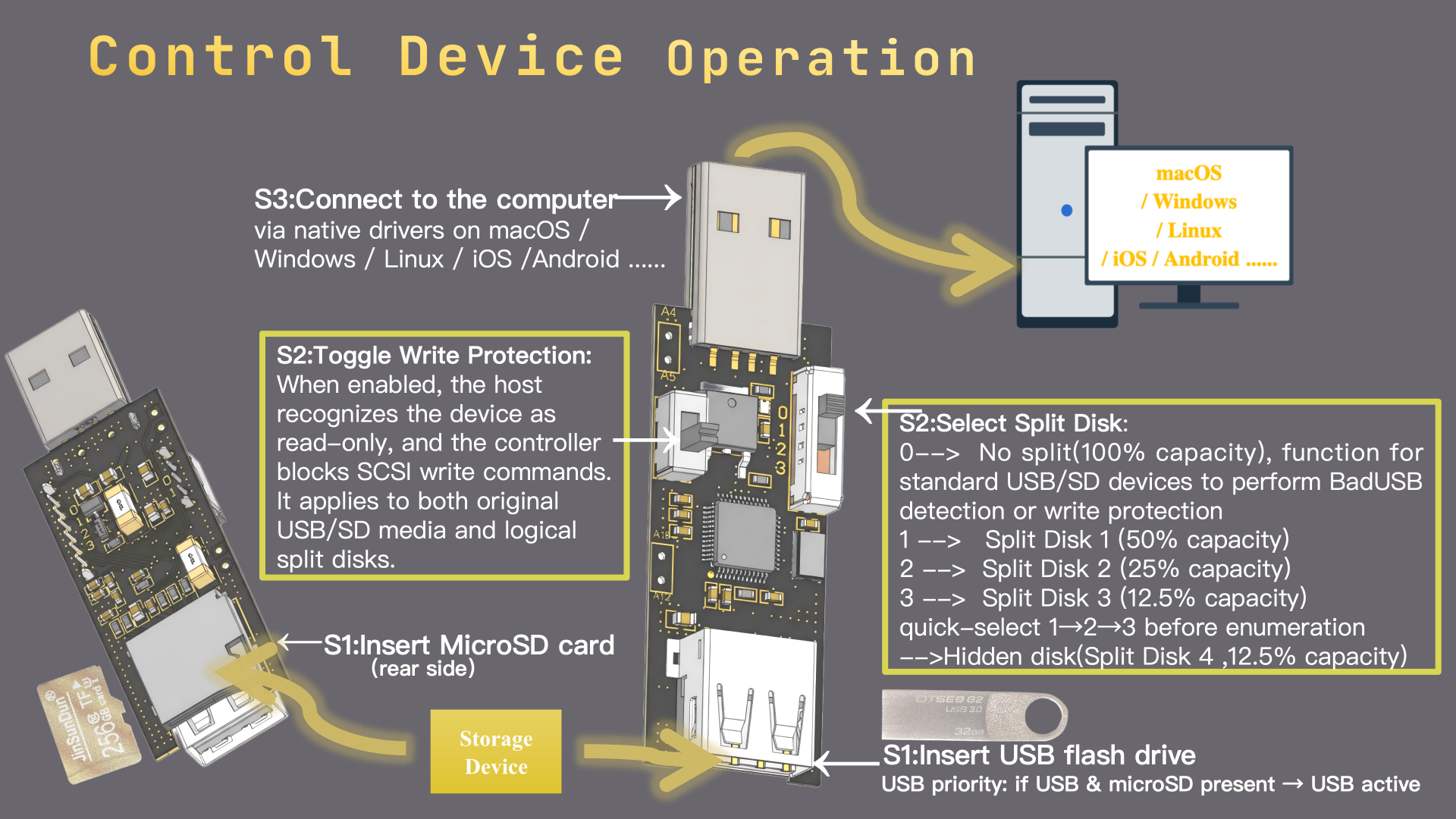

E. From concept to reality: a general-purpose, lightweight, and capable controller

To realize the idea, I implemented it as a general-purpose USB controller adapter, focusing on function while keeping the design simple and elegant.

As the video shows, the controller already delivers several unique capabilities:

As the video shows, the controller already delivers several unique capabilities:

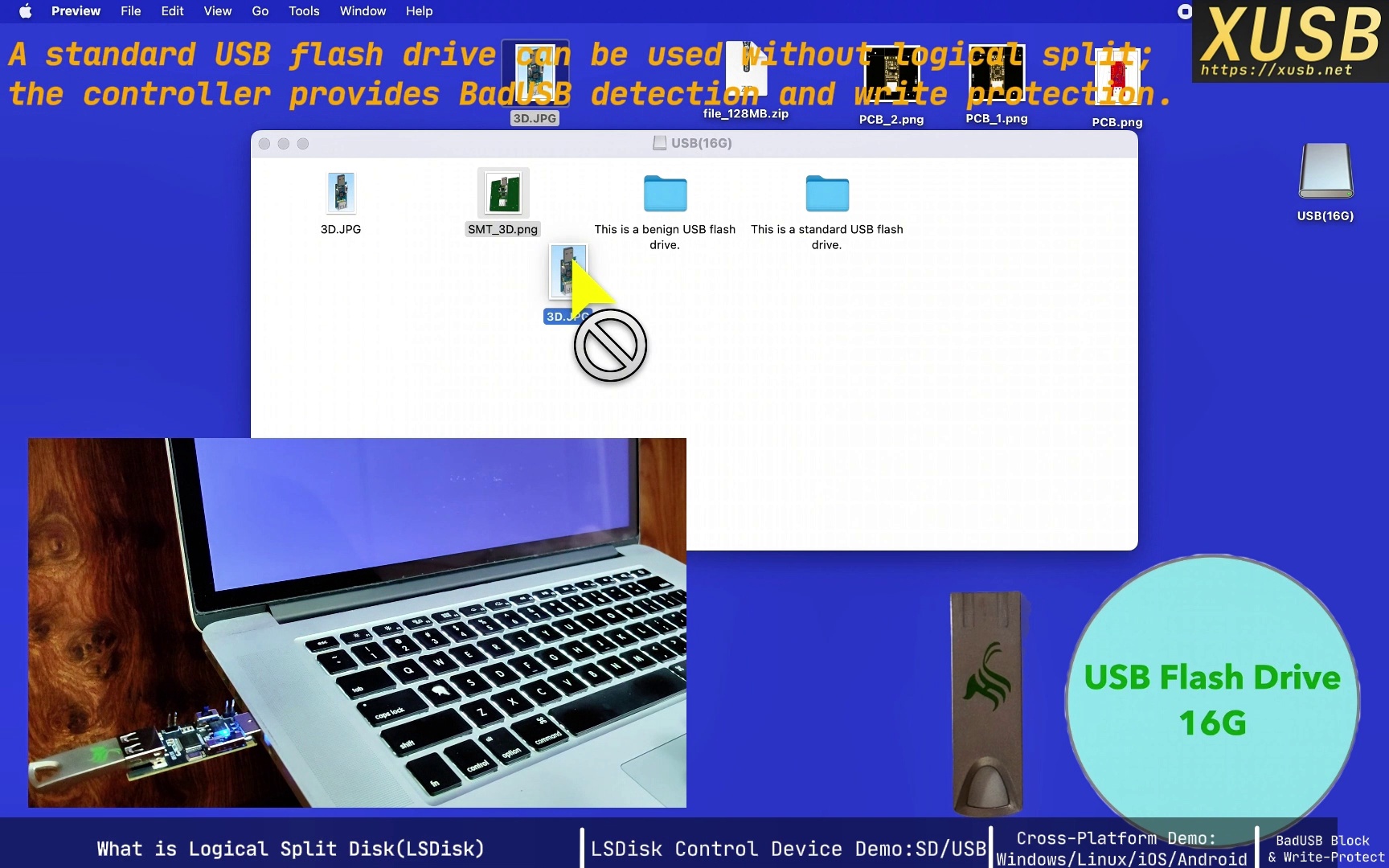

1. Broad compatibility and generality

It is OS-agnostic (no extra drivers needed on Windows, macOS, Linux, iOS/iPadOS, or Android) and independent of device type. Whether a USB stick, SD reader, or portable SSD—if the controller can talk to it, you get sector-level control. Because it truly operates at the block-device layer, it is file-system agnostic. As in the demo, you can use any file system—FAT32, APFS, EXT4—and even install full operating systems. (Note: this falls out naturally from command-level control and requires no per-OS tailoring.)

2. Multiple “physical” disks from the host’s perspective

One physical device becomes four (or more) logically independent drives. In the demo, an SD card is split into four logical disks. They coexist on one card, yet the host cannot detect the others in any way. The same applies to USB-stick demos.

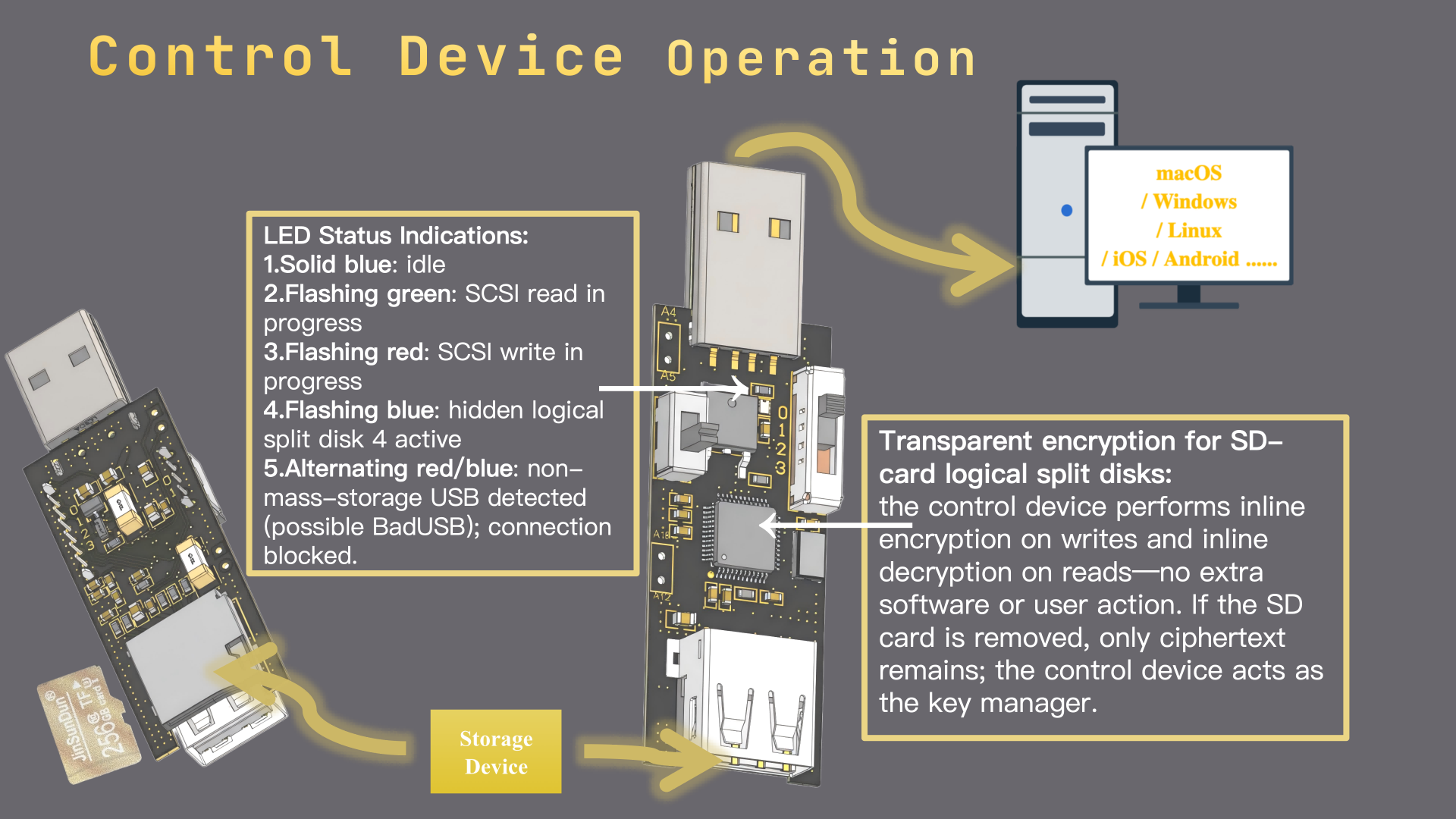

3. Transparent hardware encryption

The controller recognizes all host I/O (e.g., SCSI READ (10)/WRITE (10)), encrypts data on write and decrypts on read—transparently. Remove the card and insert it into a normal reader and you’ll see unreadable noise. The control device effectively acts as the key and can be stored separately from the medium. Even if the medium is lost or stolen, data remains protected so long as the key (the controller) is safe. Unlike OS-level software encryption, there’s no key residue in system memory. (Note: another natural outcome of command-level control, enabling low-complexity, transparent hardware crypto.)

4. Write-protect ordinary USB drives

When enabled, the controller declares the device read-only and the OS marks it so. For example, on SCSI MODE SENSE (10) the controller returns the read-only flag; “New,” “Delete,” and drag-to-write disappear. Any attempted writes are rejected at the controller (e.g., SCSI WRITE (10)). This protection is implemented in hardware, not via OS file permissions. You can enable it on a common drive with no physical lock, or on a specific logical disk. (Note: this reproduces the effect of dedicated “USB write-blockers” with far less complexity.)

5. Unique hidden logical disks

Specific DIP-switch combinations can reveal “hidden” disks that remain invisible under other combinations, illustrating multi-purpose scenarios for LSDisk.

6. Real-time read/write status

LEDs expose low-level I/O in real time: blue = idle, green = reading (e.g., SCSI READ (10)), red = writing (e.g., SCSI WRITE (10)). This “physical-layer monitor” lets you verify host behavior at a glance and adds a layer of transparent trust.

7. Extra protection against BadUSB

The controller only allows standard Mass-Storage-Class devices. Attempts to masquerade as non-MSC (e.g., a keyboard via HID injecting malicious commands—classic BadUSB) are rejected; the LED alternates blue/red as a warning. (Note: command-level control allows the controller to act as a BadUSB detector/guard.)

8. Lightweight and efficient

The core algorithms use minimal CPU and memory, running efficiently on an MCU (microcontroller unit). This prototype uses a 120 MHz MCU and supports USB 2.0 High-Speed. The design can be an external adapter or an IP core integrated into embedded systems—U-disks, HDD/SSD controllers, or storage chips. Automotive/industrial designers can carve one large chip into independent firmware, logs, user data, and black-box regions—cutting BOM (bill of materials) cost and complexity. Additional logical regions can even be provisioned remotely via OTA (over-the-air) with negligible load on the main SoC.

(Full demo video. overview and driver-free compatibility tests on Windows, macOS, Linux, iOS/iPadOS, and Android.)